As most of the Bay Area was settling in to watch game 3 of the World Series, fans of the Oakland A's and San Francisco Giants could think of little else. All eyes were on Candlestick Park on that warm fall day in October 1989, and no one could have predicted the disaster that was just moments away.

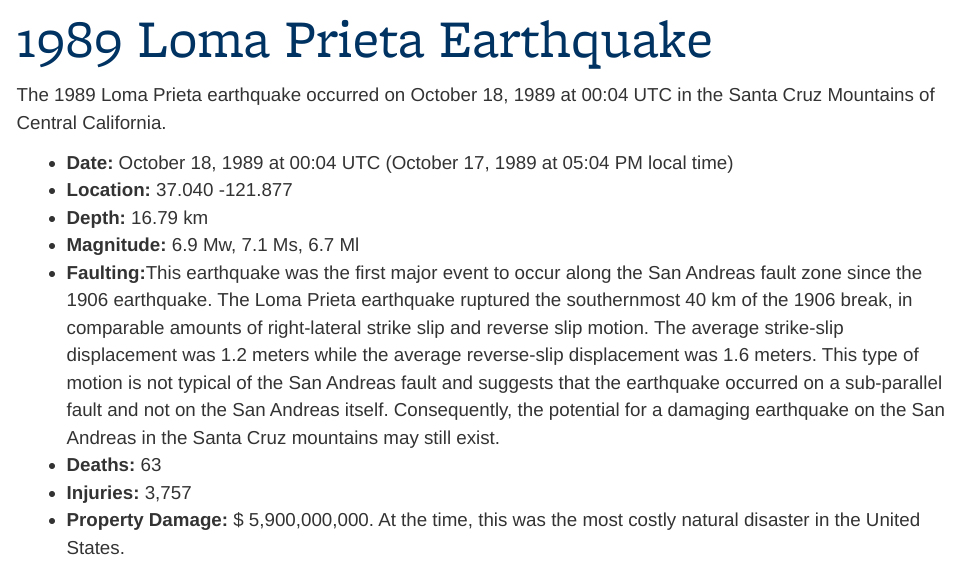

Centered in Santa Cruz County, on a section of the San Andreas Fault and with a magnitude of 6.9, the quake that shook the Bay Area 34 years ago today was responsible for 63 deaths, 3,757 injuries, and an estimated 6 billion in damage.

While "The Big One" wasn't expected during the "Bay Bridge Series," the quake was a doozy. Originally pegged at a whopping 7.1 on the magnitude scale and later downgraded slightly, Loma Prieta was larger and deadlier than any earthquake most Bay Area people could recall, and those 15 seconds of shaking would change many things in the years to come.

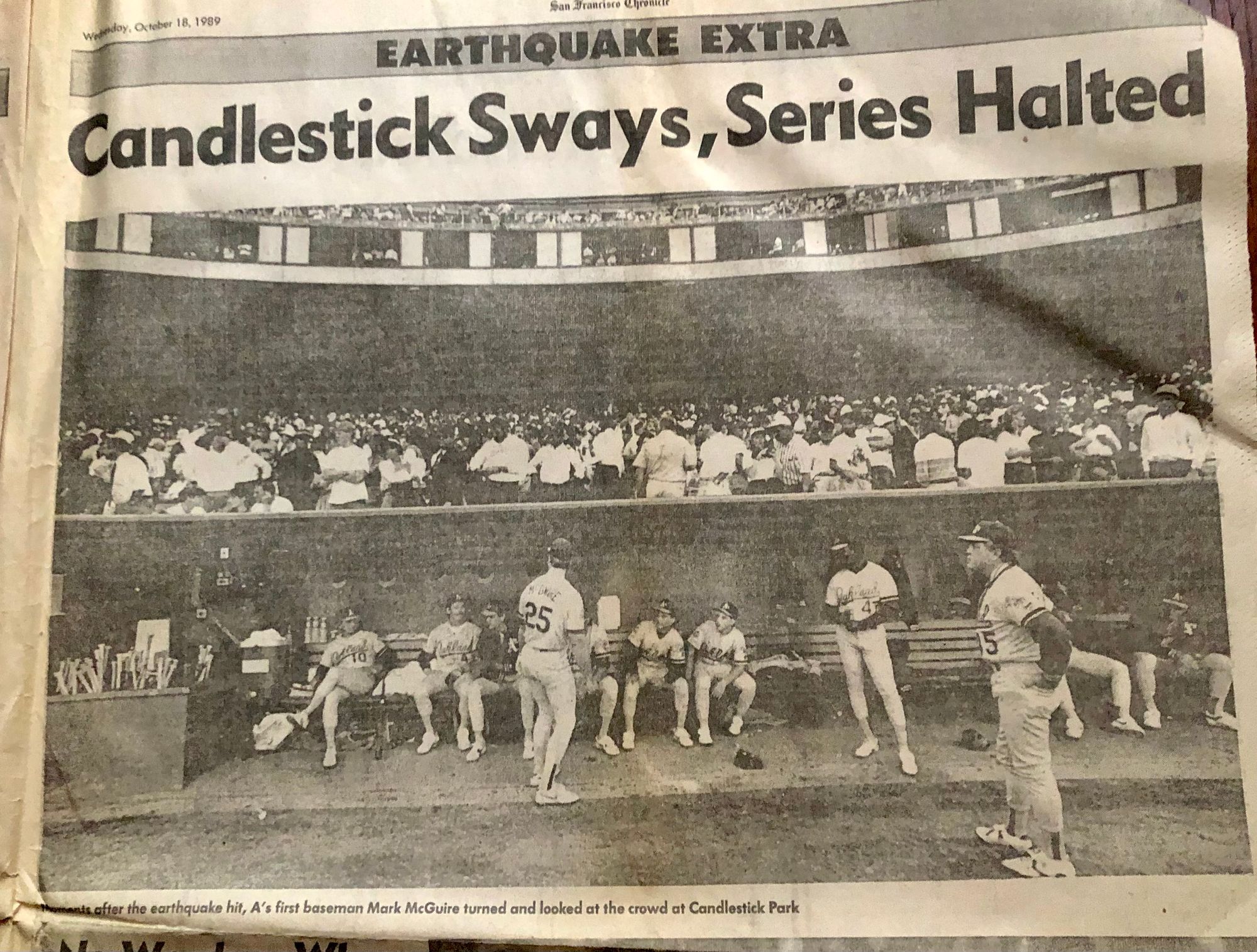

San Francisco Chronicle, October 18, 1989.

Loma Prieta caused major damage to both Oakland and San Francisco, along with other parts of the Bay Area, leaving many communities without power or working telephones. With the internet still years away, communication in parts of Northern California was brought to a grinding halt.

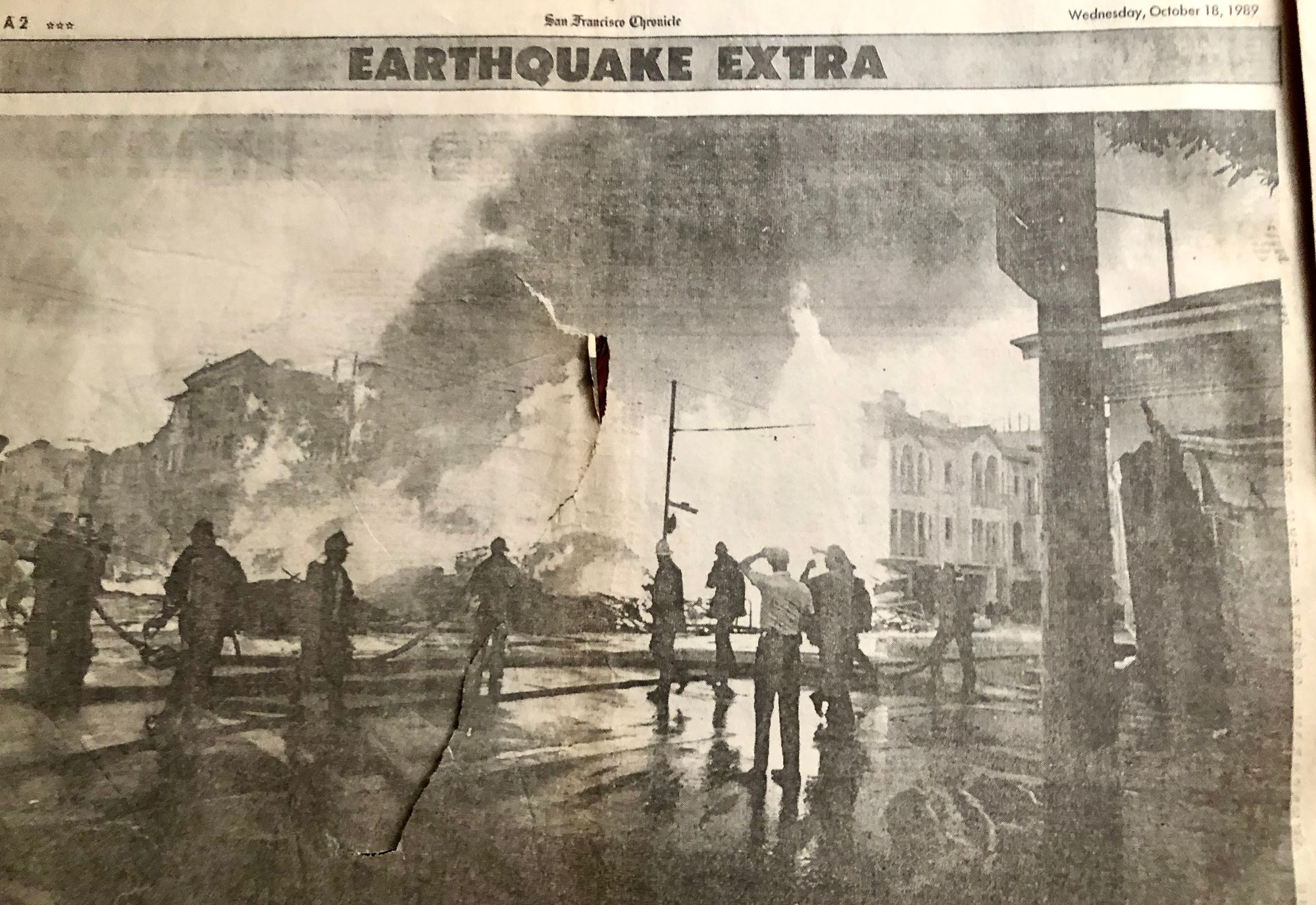

In Oakland, the Cypress Street Viaduct collapsed, pancaking the top of the structure onto its lower level, instantly reducing cars stuck in evening traffic to squashed chunks of metal. The Bay Bridge's upper deck lost a section, separating the East Bay from San Francisco and stranding hundreds. Candlestick Park suffered damage to its upper deck as pieces of concrete fell from in front of dismayed baseball fans. As the sun went down, homes in the Marina District burned, ignited by leaking natural gas lines ripped apart from the jolt and its many aftershocks. Looking west from the East Bay, this was the only light visible in San Francisco.

In Richmond, no homes collapsed, but many buildings were damaged, including the historic Ford Assembly Plant, and everyone had a story to tell about exactly where they were at 5:04 p.m when the ground started to move.

Current Richmond resident and photographer Ed Shelden remembers it this way.

"I was sitting in my living room in Walnut Creek, waiting for the World Series to start. My big yellow cat was stretched out on the floor. The building shook, the power went and the cat shot out the door. After checking on my parents in Richmond, I was heading Westbound on I-80 near Aquatic Park. San Francisco was almost all dark. The fire burning in the Marina District was very bright. I thought that I was looking at a dazzling bright road flare," Shelden recalled.

In the aftermath of the quake, along with the cleaning and repair work, came the realization that perhaps Loma Prieta hadn't been the "big one" after all and that a larger, more devastating earthquake could be possible in the near future.

According to the US Geological Survey, there is a probability of 72 percent that an earthquake measuring magnitude 6.7 will occur in the next 30 years in the San Francisco Bay area.

The Hayward fault runs through densely populated areas, including Richmond, El Cerrito, Berkeley, Oakland, San Leandro, Castro Valley, Hayward, Union City, Fremont, and San Jose, while the San Andreas lies just west, cutting through the western part of San Francisco and down the peninsula.

Evidence of seismic activity is easy to find in Richmond, with one notable place being Alvarado Park. With the fault line cutting through San Pablo's Riverside Elementary into the park and up Arlington Avenue to Bernhard Avenue, the movement of earth and structures is visible, especially to those who live in the area.

Sherden said there's a system for tracing the Hayward fault line through the East Bay.

"There is the old story of how to find the Hayward Fault. Get a map of the East Bay. Start checking off the schools (old & current) from Hayward State to Riverside school, and you can see a close location of the Hayward fault," he said.

In the months and years following Loma Prieta, earthquake preparedness as we know it today was developed, and while many people already knew the basics prior to the quake, more took notice after, with organizations and groups who specialized in disaster training beginning to pop up.

MyShake is a mobile app developed by seismologists at UC Berkeley designed to alert the user to an impending earthquake.

According to the website, "MyShake is the citizen science project bringing users together to build a global earthquake early warning network. Our app keeps you informed about earthquakes and monitors for them using data from your phone’s sensors. Our goal is to build a worldwide earthquake early warning network so that communities can reduce the impact of earthquakes. Since MyShake uses smartphones as earthquake sensors, it can be used everywhere - even in countries without access to traditional seismic technology."

California's Great ShakeOut is part of International ShakeOut Day, falling this year on October 19, when millions of people worldwide will participate in earthquake drills at work, school, or home.

In Richmond, there are two groups, CERT and REACT, which specialize in preparedness for all types of disasters, including earthquakes.

REACT/CERT training is currently free to any citizen, neighborhood, school, church, employee, or business in the City of Richmond. To find out more, please contact the Office of Emergency Services at (510) 620-6866.

HomepageGovernment Websites by CivicPlus®

HomepageGovernment Websites by CivicPlus®Help keep our content free for all!

Click to become a Grandview Supporter here. Grandview is an independent, journalist-run publication exclusively covering Richmond, CA. Copyright © 2023 Grandview Independent, all rights reserved.